We All Go Through The Oblivion Curve, But… Do You Know What It Is?

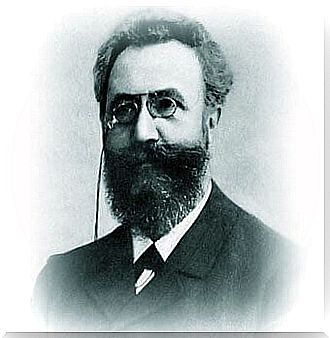

It was Ebbinghaus (1885) who was the first to systematically study how we forget as time passes. We are all aware of this phenomenon in an intuitive way, that’s why we pass on that information that we want to keep in our memory, thus preventing it from being erased over time. So we all slide along the curve of oblivion, even if we don’t realize it.

The most curious thing is that to research this phenomenon, which happens to all of us to a greater or lesser extent, but in a similar way, Ebbinghaus was its own object of experience. In this way, he ended up defining what is now known as the forgetting curve.

As we say, Ebbinghaus was the first psychologist to scientifically study memory, or at least the first to try. He graduated from the University of Bonn, where he obtained his doctorate in 1873. He developed his entire career as a memory researcher with a very clear idea: quantitative methods of analysis were applicable to higher mental processes.

In other words, Ebbinghaus thought that in psychology it was possible to measure and measure right. For this, he had no doubt in taking as a reference variable one that we all use: time. In your case, the time of oblivion.

He performed a great deal of very reliable experiments for the experimental control instruments he had at the time. With these experiments, he tried to unravel the functioning of memory based on a series of laws.

For example, he performed a test in order to explore memory, known as the “gaps test”, based on repeating sentences where some words had purposely been omitted. With this study I not only hoped to be able to work on understanding the nature of learning and forgetting, but also that it would have practical value in the educational field.

Much of the criticism that his research findings have received is based on the fact that his interest is actually in the acquisition of verbal repetition habits rather than memory searches as operates in everyday life situations. That is, it is claimed that their results are great for controlled laboratory conditions, but that in real life memory is subject to conditions that can hardly be replicated, such as motivation, unintentional repetition or the influence of emotional impact.

His works include The Intelligence of School Children (1897), Memory (1913), Textbook of Experimental Psychology, vol. 1 (1902), vol. 2 (1908). Before talking about the forgetting curve, it is necessary to know some basic aspects about memory and learning that will help us to better understand the importance of this curve.

What is learning?

It is not easy to formally define learning because there are so many different perspectives. Each of them emphasizes a different facet of this complex process. A definition of learning could simply refer to the behavior that can be observed.

For example, the fact that someone drives a car well shows that that person has learned to drive. Another definition of learning could also refer to a state of inner knowing that could be demonstrated, in turn, by providing examples of how this theory is proven.

Many dictionaries define this type of learning as “knowledge acquired through study”. In everyday language we say we know the Greek alphabet, the names of the bones in the inner ear or the stars of the constellation Cassiopeia. Both perspectives (observable behavior and interior state) are important points of view and compatible with the contemporary theory of learning.

Thus, learning can be defined as follows: “Learning is a change that takes place in an organism’s mental state, which is a consequence of experience and relatively permanent influence on the organism’s potential for later adaptive behavior.”

Ebbinghaus’s research

Association laws directly influenced learning research. There is no better example of this than the work of Ebbinghaus (1850-1909). According to him, the development of an association between two mental events could be better studied using stimuli that were devoid of any previous association.

Precisely, seeking to work with stimuli that had no meaning, Ebbinghaus used the so-called nonsense syllables (BIJ or LQX) which he considered to have no inherent meaning. Ebbinghaus spent a lot of time associating one stimulus with another, and then repeating them.

Working in this way and with this type of stimuli (meaningless syllables), he directly put to the test many of the association’s principles, developed more than 100 years earlier. For example, it determined whether stimuli written together in the list would associate more firmly than syllables that were not close together.

Ebbinghaus’ research confirmed many of the ideas first proposed by British empiricists. For example, that proactive associations are stronger than retroactive ones (if the syllable “A” precedes the syllable “B”, then “A” evokes the memory of “B” better than “B” the memory of ” THE”). Interesting, isn’t it?

The memory

Studying learning is studying memory and, therefore, also the forgetting curve. Remember that learning would not be possible without memory because each execution of a learned reaction requires recall (partial or full) of the previous rehearsal.

memory phases

What is stored in our memory, what we learn, goes through at least three phases: encoding, storing and retrieving. In the first phase of any learning, what we do is encode information, translate it into the language of our nervous system and in that language give it a place in our memory.

Second, during the retention or storage phase, information or knowledge persists over time. In some cases this phase can be quite brief. For example, information in short-term memory lasts only 15 to 20 seconds or so.

In other cases, storing a memory can last a lifetime. This form of storage is called “long-term memory”. Thirdly, the recovery or execution phase is the one where the individual remembers the information and gives the answer, offering evidence of having previously learned it.

If execution is adequate in relation to the levels demonstrated during acquisition, we say that forgetting is minimal. However, if execution slows down significantly, we say that forgetting has occurred. Furthermore, in many cases it is simple to quantify how much was lost, how long it took to lose a real part of what was previously encoded.

Why does the forgetting curve happen?

A fundamental challenge for psychology is to understand why memories persist once they are encoded or, conversely, why forgetting occurs after learning. There are several approaches that try to answer these questions.

Storage theories

Some storage theories focus on what happens to information during the storage phase. For example, the decay theory states that forgetting happens because memories weaken, or decay in strength, during the retention interval. It’s something similar to what happens with footprints in the sand on the beach.

While some evidence supports this view, few contemporary theorists describe forgetting in terms of memory decay.

On the other hand, the interference theory states that forgetting happens because memory elements that compete with others are acquired during the retention interval. For example, acquiring new information can cause us to forget previous information (retroactive interference). It happens when a problem has many complex statements instead of one simple one.

Likewise, the presence of previous information can interfere with the expression of a newly formed memory (proactive interference). For example, we’ll better remember someone’s phone number if it’s similar to ours.

Recovery theories

Recovery theories claim that forgetting is the consequence of an error in retrieving information during the execution phase. That is, the memory element “survives” the retention interval, but the subject simply cannot access it.

A good analogy would be looking in a library for a book kept out of place on the shelves. The book is in the library (the information is intact) but it cannot be found (the subject cannot retrieve the information). Much of contemporary memory research supports this view.

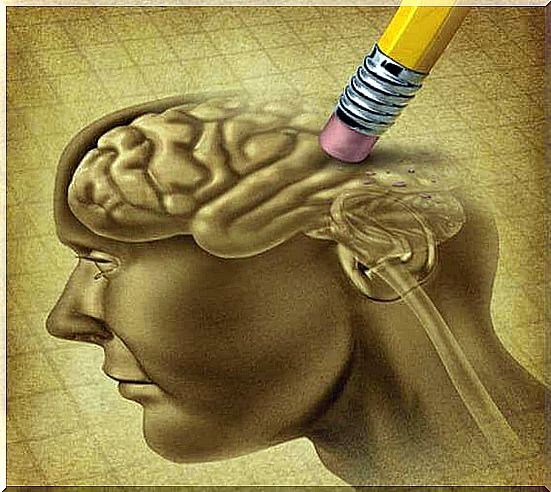

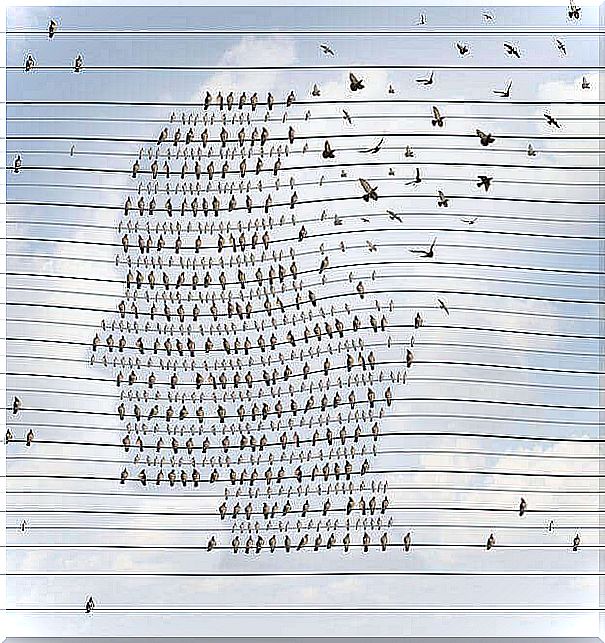

The Ebbinghaus Oblivion Curve

Simply passing time seems to have a negative effect on retention capacity. As already mentioned, Ebbinghaus (1885) was the first to systematically study the loss of information in memory over time, defining what is known as the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. The concept “curve” refers to the graph resulting from your searches.

We have already seen that he himself was the object of his research and that the research consisted of learning lists of thirteen syllables, which he repeated until making no mistake in two successive attempts. Subsequently, it assessed its retention capacity at intervals between twenty minutes and one month. From this kind of experience, he built his famous forgetting curve.

What were the results obtained by Ebbinghaus?

These results try to explain how long it is possible to preserve a content in memory if it is not sufficiently remembered. The results found in their research showed that forgetting happens even at shorter intervals. Furthermore, he found that with material that was not significant and therefore unassociated, forgetting increased as time went on, very early on and more slowly thereafter. So if we were to graph this information we would see how the forgetting curve is shaped like a logarithmic curve.

In this way, the forgetting curve illustrates the loss of memory over time. A related concept is recall intensity, which indicates how long a content is preserved in the brain. The more intense a memory is, the longer it holds.

A typical forgetting curve graph shows how in a few days or weeks we forget half of what was learned, if not remembered. It also found that each review allows the next to go further back in time to retain the same amount of information. So if we want to remember something, maybe the first review should be done in an hour, so the next review can be done when more time has passed.

oblivion curve

The memory curve takes a very sharp drop when it comes to memorizing meaningless material, as Ebbinghaus did. However, it is almost flat when it comes to traumatic experiences. On the other hand, a slight drop may occur, not so much because of the characteristics of the information, but because the information is implicitly revised (eg, reliving experiences, using the alphabet to look up in a dictionary).

A practical example of how quickly we forget data, and therefore the forgetting curve, if there is no immediate review is the following: one day after studying and not reviewing, it is possible to forget up to 50% of what was studied. Two days later, what you will remember doesn’t reach 30%. A week later, you’ll be lucky if you can remember more than 3%.

Bibliography:

- Tarpy, R. (2000). Learning: Contemporary Theory and Investigation. Madrid: McGraw Hill.

- Bower, G. Hilgard, E. (1989) Teorías del Aprendizaje. Mexico: Trails. Poisons for our memory