“Wild Children” And Their Behavior In Society

One of the great debates that occupies an important part in our history concerns the influence of society on childhood. Two great authors of this debate were Jean-Jacques Rousseau on one side and Thomas Hobbes on the opposite. His reflections were about the goodness and badness of humanity, two themes that, as we will see below, were related to the so-called “wild children”.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1896) argued that man is by nature good and society corrupts him. In turn, Hobbes (1588/2010) coined the famous phrase “man is the wolf of man”, which means that man is evil by nature and it is exactly the mechanisms of social control that prevent this evil from destroying us .

But how to know who was right? Although it is impossible to separate a child from society to prove it for moral and ethical reasons, there are children who, due to different circumstances, were raised in isolation from society. These cases were called “wild children”.

“Wild children” are people who for a part of their childhood lived outside of society, this includes both children who have been confined and children who have been abandoned in the wild. Even if there are few cases and even if in some the veracity of the isolation has been questioned or if they are just myths of little credibility, there are more than twenty cases that, with greater or lesser rigor, have been documented and studied.

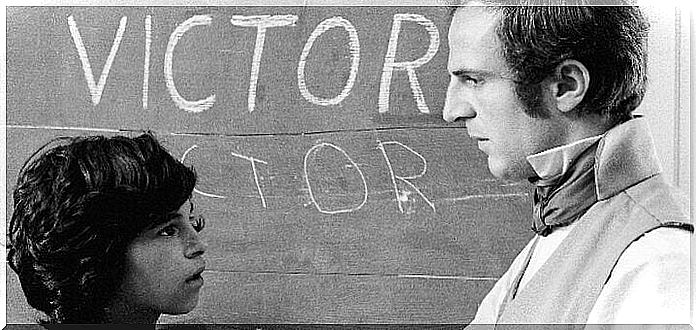

Victor of Aveyron

Possibly the most famous case of a wild child is the case of Victor de Aveyron. Víctor (Itard, 2012) was captured when he was approximately eleven years old. At the end of a week, he escaped and, after spending the winter, was captured again while hiding in an abandoned house. He was admitted to a hospital, where he began to study his case.

One of the most widely accepted theories about Víctor’s case is that he suffered from an autistic spectrum disorder. Due to the strange behaviors he exhibited, his family abandoned him. Besides, the various scars Víctor had were not from wildlife. They corresponded to physical abuse prior to the time he was found in the forest.

According to one of the doctors who took care of his case (Itard, 1801), Víctor was “an unpleasantly dirty child, who presented spasmodic movements and even convulsions. He swayed incessantly like a zoo animal and bit and scratched anyone who came near. The boy showed no affection for the people who took care of him and, in short, he was indifferent to everything and paid no attention to anything”. Although his physical appearance improved, as well as his sociability, attempts to teach him to speak and behave in a civilized manner were unsuccessful.

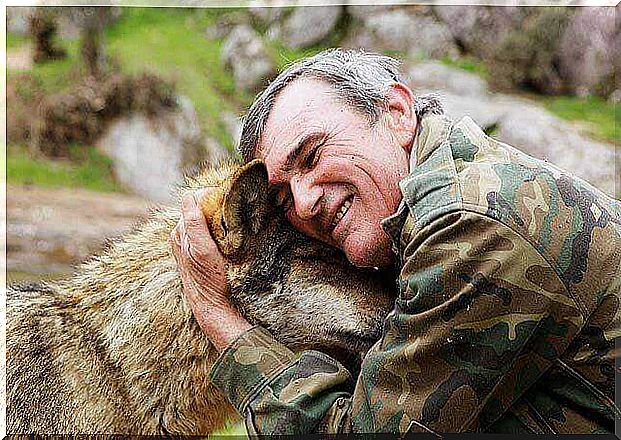

Marcos Rodríguez Pantoja

Although there are several cases of “wild children” who lived with animals such as goats, dogs, gazelles, wolves, monkeys, etc., many are discredited by the lack of data to prove their authenticity. However, Marcos’ case stands out for being recent and proving. Marcos was sold by his parents at the age of seven to a landowner who handed him over to a goat herder with whom he lived until his death in a cave. After the goat herder’s death, Marcos was alone for eleven years until he was found by the Civil Guard. During those eleven years, his only company was the wolves.

The case study was carried out by anthropologist and writer Gabriel Janer Manila (1976). The cause of their abandonment was linked to a socioeconomic context of extreme poverty. The skills Marcos learned before his abandonment, along with his natural intelligence, were the aspects that made his survival possible. During his isolation, Marcos learned the noises of the animals he lived with and used them to communicate with them, while slowly abandoning human language.

After being reintroduced into society, a readaptation to human customs began. Despite this, even in adult life he showed a preference for life in the countryside with animals. He also developed an aversion to the noise and smell of cities. Marcos continued to believe that life among humans is worse than life with animals.

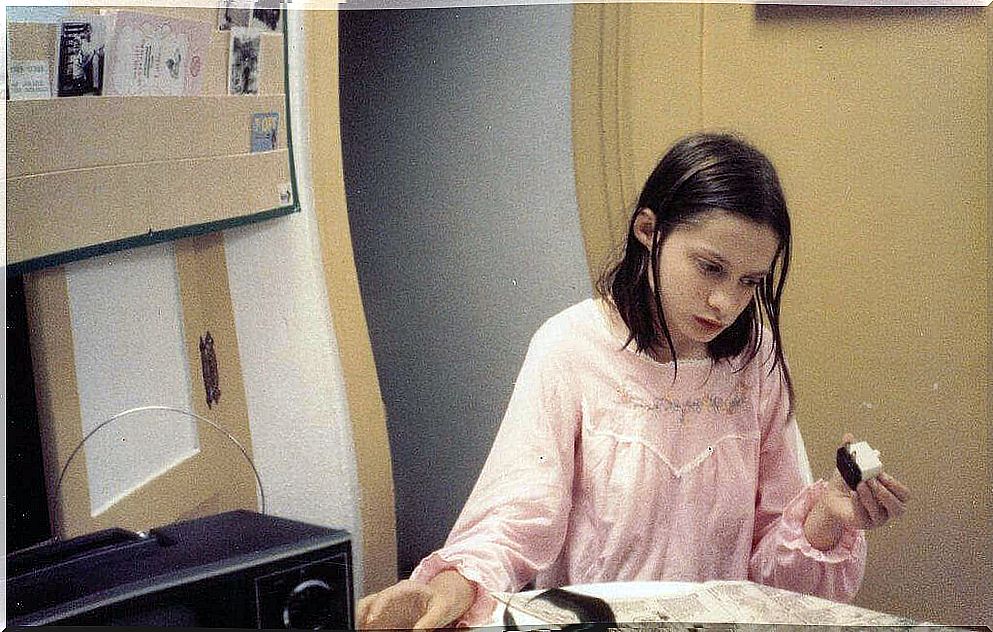

genius

Genie’s parents (Rymer, 1999) were in trouble, her mother was blind from a retinal detachment and cataracts, and her father was plagued by depression that worsened when her mother died in a car accident. Genie later began to say that most children and doctors diagnosed that she was probably mentally handicapped. So her father, afraid that the authorities would take his daughter, felt he should protect her from the dangers of the outside world.

Genie was kept in her own room and had contact only with her father. Genie had been banned from making noise and spent her nights in a cage. Their diet consisted mainly of baby food. At the age of 13, she understood only 20 words, most of which were short and negative: “stop, that’s enough, no…” The girl’s room was completely closed, there was only a small hole that allowed her to see two centimeters of the world. The other residents of the house had been forbidden to visit her or even to speak to her.

Finally, Genie’s mother escaped with her and her brother, which allowed the girl to be put into treatment (Reynolds y Fletcher-Janzen, 2004). The first part of the treatment was carried out by isolating the girl from her mother and the conclusion was that she had experienced an involution. She was worse off than when she was found. Then, it was returned to the mother, who realized that it was very difficult to take care of the girl, who had been through several foster homes and, in some, had even been mistreated again.

Rochom P’ngieng

Rochom (El País, 2007) was a Cambodian girl who got lost in the jungle at the age of 9, and only reappeared 10 years later. After disappearing on her parents’ farm, she was found, after ten years with no news, by a farmer who turned her in to the police.

Upon returning to society, Rochom could not bear to put on clothes, could not remember how to speak and emitted grunts. She walked on a squat, and when left alone, she tried to escape. The various scars she had made it possible to believe that she might have been held captive and even abused (The Guardian, 2007). Later, Rochom escaped and was found 10 days later in the sewer. She was rescued and admitted to a hospital where, according to her parents, she was without strength, sleeping all day. She was pale and weak.

Insertion in society

The return of these “wild children” to society was not easy. Some factors such as the degree of isolation and the age they had when leaving society are decisive when it comes to understanding their behavior in society (Singh y Zingg, 1966). The “wild children” who were deprived of any contact with humans, who didn’t even see humans, will present more problems. Those who have lived among animals may adapt better.

Vicarious learning is a very important part of development and those who have missed this stage will find it more difficult to perform behaviors they have never seen performed. Stimulus deprivation when you are little will delimit the experiences of these children (McCrone, 1994). In this sense, isolation can even limit bodily movements and cause physical malformations. Other basic skills such as spatial memory may not develop in isolation situations.

On the other hand, especially for “wild children” who have lived with animals, naturalistic intelligence (Gardner, 2010) is usually well developed. This intelligence is the ability to perceive the relationships between species, groups of objects and people, recognizing the differences and similarities between them. The individual specializes in identifying, discerning, observing and classifying members of groups or species of flora and fauna, the efficient use of the natural world being his field of observation.

However, the lack of interaction with other people and emotional bonds are basic skills that “wild children” will not develop. Because of this, and the large cultural component of emotions and their regulation, these children have difficulties in adapting to these unwritten norms that govern the functioning of any society.

Communication in “wild children”

Language development is another central point. Humans, at birth, are capable of making over 200 different sounds. Society, through reinforcement, will indicate which of these sounds correspond to the language or languages that the children will speak. Those children who do not receive this reinforcement from an early age will find it more difficult to pronounce correctly. The same thing happens with grammar.

Linguist Noam Chomsky (1957/1999) proposed that there is a time limit for learning a language naturally. This period is around three years of age and, once this time has passed without the child learning a language, he will no longer be able to develop the brain structures necessary to learn. Despite being able to learn words, complete mastery of the language will require extraordinary effort.

As Chomsky proposes, at birth we have innate brain structures. These structures that formed evolutionarily are preprogrammed to develop certain behaviors or actions such as speech. However, if these structures do not receive the necessary stimuli for them to complete their development before a certain point, they will cease to be useful and will not fulfill their purpose. Furthermore, it is necessary that the development of these structures take place at the same time as that of other brain structures.

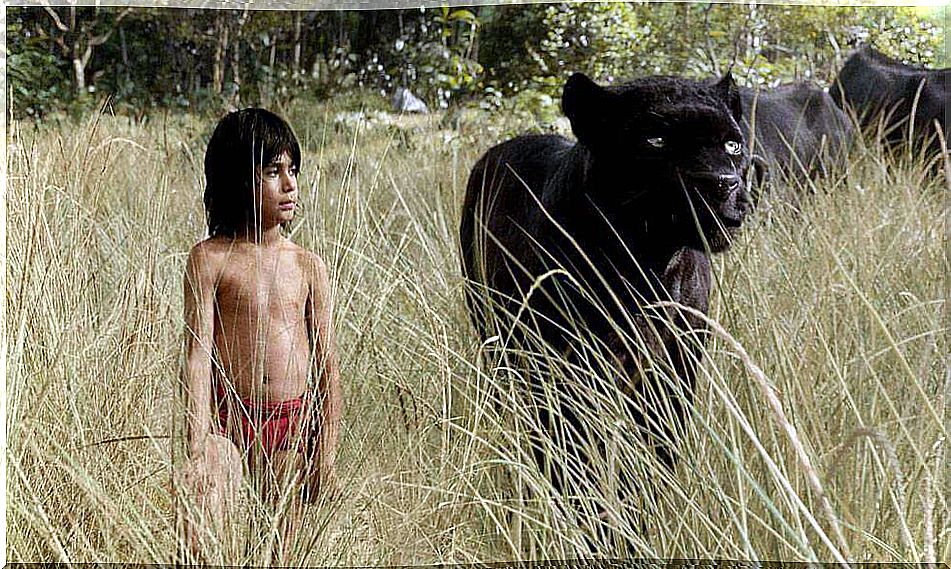

The “wild children” off screen

The image of Mogli, the wolf boy created by the writer Rudyard Kipling (1894) does not correspond to the reality of “wild children”. Likewise, we cannot refer to Tarzan either. The deprivations that these children have suffered do not make them revolutionaries when they return to society.

The prospects for the future for “wild children” are usually not good. After having been deprived of stimuli and experiences common to the human species, they will go through critical periods to develop certain skills, such as language.

These shortages or lack of skills are preceded by a lack of encouragement and reinforcement so that the development of these skills can take place. As we said, deprivation at a critical stage can impede the full development of skills such as language or spatial memory. All of this, together with the difficulty that their treatment poses for therapists, complicate education and reinsertion.

One of the worst consequences for these “wild children” is that their life expectancy is very short. It may be that these children were not prepared for society, just as it may be that society was not prepared for them. In this sense, the debate about the goodness and badness of human beings and about the controlled or degrading character of society remains open.

Bibliography:

Singh, JAL and Zingg, RM (1966). Wolf-children and feral man. Mishawaka: Shoe String Pr Inc.

Chomsky, N. (1957/1999). Syntactic structures. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

El País (2007). The last niña salvaje. Found at: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2007/01/19/actualidad/1169161205_850215.html

Janer Manila, G. (1976). The educational issue of wild children: The case of “Marcos”. Found at: http://www.raco.cat/index.php/AnuarioPsicologia/article/viewFile/64461/88142

Gardner, H. (2010). The reformulated intelligence: The multiple intelligences in the siglo XXI. Barcelona: Paidós.

Hobbes, T. (1588/2010). Leviathan. Revised Edition, eds. AP Martinich and Brian Battiste. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Itard, JMG (1801). From the education of a homme sauvage or from the premiers developpemens physiques et moraux du jeuneççs sauvage de l’Aveyron. Paris: Goujon.

Itard, JMG (2012) El niño salvaje. Barcelona: Artefakte.

Kipling, R. (1894). The jungle book. United Kingdom: Macmillan Publishers.

McCrone, J. (1994). Wolf children and the bifold mind. In J. McCrone (Ed.), The myth of irrationality: The science of the mind from Plato to Star Trek. New York: Carroll & Graf Pub.

Reynolds, CR, Fletcher-Janzen, E. (2004). Concise encyclopedia of special education: A reference for the education of the handicapped and other exceptional children and adults. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 428-429.

Rousseau, J.-J, (1896). Du contrat social (El social contract). Paris: Felix Alcan.

Rymer, R. (1999). Genie: The scientific tragedy. UK: Harper Paperbacks.

The Guardian (2007). Wild child? Found at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jan/23/jonathanwatts.features11